|

|

The sidesplitting story of the midpoint polygon

The Mathematics Teacher; Apr 1994; 87, 4; Social Science Premium Collection

pg. 249

The_sidesplitting_story_of_the.pdf

(577.45 KB, Downloads: 104)

The_sidesplitting_story_of_the.pdf

(577.45 KB, Downloads: 104)

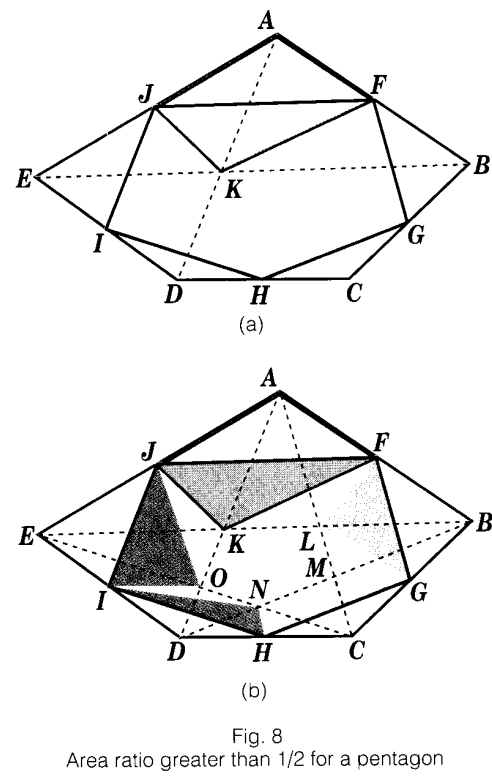

Area ratios greater than $1 / 2$. In figure $\mathbf{8 a}$, FGHIJ is the midpoint polygon for pentagon $A B C D E$. In $\triangle A B E$, if we choose a point $K$ (we have chosen the intersection of $\overline{B E}$ and $\overline{A D}$ ) on $\overline{B E}$ (which we know is parallel to $\overline{J F}$ from the sidesplitting theorem), then $\triangle J F K$ and $\triangle A F J$ have the same area. Similarly, in figure $\mathbf{8 b}$, $\triangle F G L$ and $\triangle F G B, \triangle G H M$ and $\triangle G H C, \triangle H I N$ and $\triangle H I D$, and $\triangle I J O$ and $\triangle I J E$, by pairs, have the same area. This process is like moving the triangles as we did with quadrilaterals. In this case the triangles, though not congruent, still have the same area. Since pentagon FGHIJ is not fully covered when the outside triangles are moved inside, the area of the midpoint pentagon is greater than half the area of the original pentagon $A B C D E .$

Area ratios less than $3 / 4$. The proof that the ares ratios for pentagons are less than $3 / 4$ is best understood in terms of what has been called flexing (Anderson and Arcidiacono 1989). Suppose that $A,B, C, D$, and $E$ are five consecutive vertices of any polygon. To flex a polygon at the vertex $C$ means that the polygon is deformed in such a way that $C$ moves along the line that passes through $C$ and is parallel to $\overline{B D}$ (see fig. 9). Notice that the area of the polygon remains unchanged because the area the moving part, $\triangle B C D$, does not change. We can also flex the polygon at $C$ even if $B, C$, and $D$ are collinear, and again, the area of the polygon does not change under flexing. We shall consider flexing that make the polygon more degenerate, that is, the polygon will approach becoming a polygon with fewer sides. For example, in figure $\mathbf{9}$, if $A B C D E$ are the vertices of a pentagon, then it becomes a quadrilateral when the vertex $C$ is translated along to the intersection of $\overleftrightarrow{C C^{\prime}}$ and $\overleftrightarrow{A B}$.

What happens to the midpoint polygon when a polygon is flexed? Let $F, G, H$, and $I$ be the midpoints of the consecutive sides $A B, B C, C D$, and $D E$ of a polygon (fig. 10). Suppose $E$ is closer to $\overleftrightarrow{B D}$ than $A$ is; then $I$ is closer to $\overleftrightarrow{G H}$ than $F$ is. Let us flex $C$ to $C^{\prime}$, Since $G H=G^{\prime} H^{\prime}=(1 / 2) B D, G G^{\prime}=H H^{\prime}$ and area $\left(\triangle G G^{\prime} F\right)$ is greater than area $\left(\triangle H H^{\prime} I\right)$ (because the height of $\triangle G G^{\prime} F$ is greater than the height of $\left.\triangle H H^{\prime} I\right)$, making area $\left(F G^{\prime} H^{\prime} I\right)$ greater than area $(F G H I)$. Since the area of the original polygon does not change, we have increased the area ratio by flexing. (If we had flexed $C$ to $C^{\prime \prime}$, a similar argument shows that the area ratio decreases. If we flex $C$ past $C^{\prime}$ or $C^{\prime \prime}$, then the pentagon becomes nonconvex.) The limit for the area ratio by flexing at any vertex occurs when the vertex becomes collinear with an adjacent side.

We can then show that the area ratio of a convex pentagon is less than $3 / 4$. Figure $\bf11$ shows the process of flexing pentagon $A B C D E$ four times into a limiting triangle. Figure $\bf11 a$ shows pentagon $A B C D E$ and its associated midpoint pentagon $F G H I J$. First we flex $B$ to $B^{\prime}$ on $\overleftrightarrow{D C}$ ) because $E$ is closer to $\overline{A C}$ than $D$ is [fig. $\bf11b$]). Then we flex vertex $A$ to $A^{\prime}$ on $\overleftrightarrow{D E}$ (because $C$ is closer to $\overrightarrow{B^{\prime} E}$ than $D$ is [fig. $\bf11c$]). Next we flex $C$ to $C^{\prime}$ on $\overline{B^{\prime} A^{\prime}}$ (because $E$ is closer to $\overline{B^{\prime} D}$ than $A^{\prime}$ is [fig. $\bf11d$]). (Note that $C^{\prime}$ is also $B^{\prime}$ and consequently also $G^{\prime \prime}$.) Finally we flex vertex $E$ to $A^{\prime}$ (which is also $J^{\prime \prime}$ ) (fig. 11e). In figure $\bf11e$ we see that area $\left(F^{\prime} G^{\prime \prime} H^{\prime} T^{\prime} J^{\prime \prime}\right)=3 / 4$ area $\left(A^{\prime} B^{\prime} D\right)$ as a consequence of the sidesplitting theorem for triangles. Because each step in this specific flexing process increases the area ratio, and because the resulting triangle obviously is not really a pentagon, we know that the area ratio for the original pentagon must be strictly less than $3 / 4$.

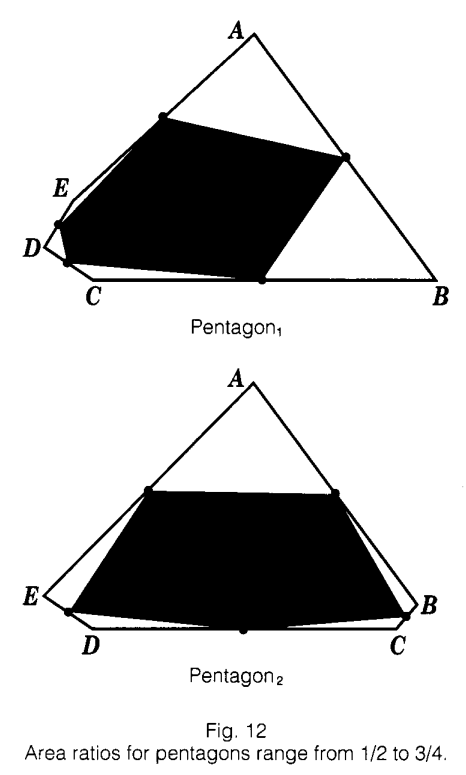

Convex pentagons exist whose area ratios are arbitrarily close to $1 / 2$ or $3 / 4$ (see pentagon1 and pentagon2 in fig. 12). By continually deforming pentagon1 into pentagon2, we obtain a family of convex pentagons whose area ratios range between the area ratios of pentagon1 and pentagon2. It follows that any number between $1 / 2$ and $3 / 4$ is the area ratio of some convex pentagon.

|

|