|

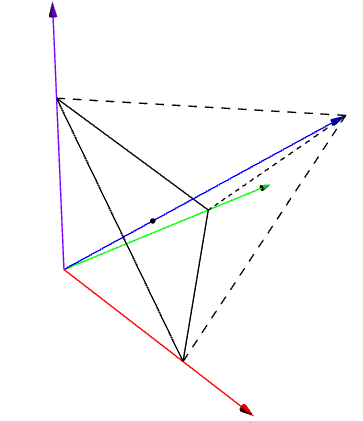

Cartesian coordinates for a regular n-dimensional simplex in Rn

One way to write down a regular n-simplex in Rn is to choose two points to be the first two vertices, choose a third point to make an equilateral triangle, choose a fourth point to make a regular tetrahedron, and so on. Each step requires satisfying equations that ensure that each newly chosen vertex, together with the previously chosen vertices, forms a regular simplex. There are several sets of equations that can be written down and used for this purpose. These include the equality of all the distances between vertices; the equality of all the distances from vertices to the center of the simplex; the fact that the angle subtended through the new vertex by any two previously chosen vertices is $\pi /3$; and the fact that the angle subtended through the center of the simplex by any two vertices is ${\displaystyle \arccos(-1/n)}$.

It is also possible to directly write down a particular regular n-simplex in Rn which can then be translated, rotated, and scaled as desired. One way to do this is as follows. Denote the basis vectors of Rn by e1 through en. Begin with the standard (n − 1)-simplex which is the convex hull of the basis vectors. By adding an additional vertex, these become a face of a regular n-simplex. The additional vertex must lie on the line perpendicular to the barycenter of the standard simplex, so it has the form (α/n, ..., α/n) for some real number α. Since the squared distance between two basis vectors is 2, in order for the additional vertex to form a regular n-simplex, the squared distance between it and any of the basis vectors must also be 2. This yields a quadratic equation for α. Solving this equation shows that there are two choices for the additional vertex:

- ${\displaystyle {\frac {1}{n}}\left(1\pm {\sqrt {n+1}}\right)\cdot (1,\dots ,1).}$

Either of these, together with the standard basis vectors, yields a regular n-simplex.

The above regular n-simplex is not centered on the origin. It can be translated to the origin by subtracting the mean of its vertices. By rescaling, it can be given unit side length. This results in the simplex whose vertices are:

- ${\displaystyle {\frac {1}{\sqrt {2}}}\mathbf {e} _{i}-{\frac {1}{n{\sqrt {2}}}}{\bigg (}1\pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {n+1}}}{\bigg )}\cdot (1,\dots ,1),}$

for $1\leq i\leq n$, and

- ${\displaystyle \pm {\frac {1}{\sqrt {2(n+1)}}}\cdot (1,\dots ,1).}$

Note that there are two sets of vertices described here. One set uses $+$ in each calculation. The other set uses $-$ in each calculation.

This simplex is inscribed in a hypersphere of radius ${\displaystyle {\sqrt {n/(2(n+1))}}}$.

A different rescaling produces a simplex that is inscribed in a unit hypersphere. When this is done, its vertices are

- ${\displaystyle {\sqrt {1+n^{-1}}}\cdot \mathbf {e} _{i}-n^{-3/2}({\sqrt {n+1}}\pm 1)\cdot (1,\dots ,1),}$

where $1\leq i\leq n$, and

- ${\displaystyle \pm n^{-1/2}\cdot (1,\dots ,1).}$

The side length of this simplex is ${\textstyle {\sqrt {2(n+1)/n}}}$.

A highly symmetric way to construct a regular n-simplex is to use a representation of the cyclic group Zn+1 by orthogonal matrices. This is an n × n orthogonal matrix Q such that Qn+1 = I is the identity matrix, but no lower power of Q is. Applying powers of this matrix to an appropriate vector v will produce the vertices of a regular n-simplex. To carry this out, first observe that for any orthogonal matrix Q, there is a choice of basis in which Q is a block diagonal matrix

- ${\displaystyle Q=\operatorname {diag} (Q_{1},Q_{2},\dots ,Q_{k}),}$

where each Qi is orthogonal and either 2 × 2 or 1 × 1. In order for Q to have order n + 1, all of these matrices must have order dividing n + 1. Therefore each Qi is either a 1 × 1 matrix whose only entry is 1 or, if n is odd, −1; or it is a 2 × 2 matrix of the form

- ${\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}\cos {\frac {2\pi \omega _{i}}{n+1}}&-\sin {\frac {2\pi \omega _{i}}{n+1}}\\\sin {\frac {2\pi \omega _{i}}{n+1}}&\cos {\frac {2\pi \omega _{i}}{n+1}}\end{pmatrix}},}$

where each ωi is an integer between zero and n inclusive. A sufficient condition for the orbit of a point to be a regular simplex is that the matrices Qi form a basis for the non-trivial irreducible real representations of Zn+1, and the vector being rotated is not stabilized by any of them.

In practical terms, for n even this means that every matrix Qi is 2 × 2, there is an equality of sets

- ${\displaystyle \{\omega _{1},n+1-\omega _{1},\dots ,\omega _{n/2},n+1-\omega _{n/2}\}=\{1,\dots ,n\},}$

and, for every Qi, the entries of v upon which Qi acts are not both zero. For example, when n = 4, one possible matrix is

- ${\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}\cos(2\pi /5)&-\sin(2\pi /5)&0&0\\\sin(2\pi /5)&\cos(2\pi /5)&0&0\\0&0&\cos(4\pi /5)&-\sin(4\pi /5)\\0&0&\sin(4\pi /5)&\cos(4\pi /5)\end{pmatrix}}.}$

Applying this to the vector (1, 0, 1, 0) results in the simplex whose vertices are

- ${\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1\\0\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}\cos(2\pi /5)\\\sin(2\pi /5)\\\cos(4\pi /5)\\\sin(4\pi /5)\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}\cos(4\pi /5)\\\sin(4\pi /5)\\\cos(8\pi /5)\\\sin(8\pi /5)\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}\cos(6\pi /5)\\\sin(6\pi /5)\\\cos(2\pi /5)\\\sin(2\pi /5)\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}\cos(8\pi /5)\\\sin(8\pi /5)\\\cos(6\pi /5)\\\sin(6\pi /5)\end{pmatrix}},}$

each of which has distance √5 from the others.

When n is odd, the condition means that exactly one of the diagonal blocks is 1 × 1, equal to −1, and acts upon a non-zero entry of v; while the remaining diagonal blocks, say Q1, ..., Q(n − 1) / 2, are 2 × 2, there is an equality of sets

- ${\displaystyle \left\{\omega _{1},-\omega _{1},\dots ,\omega _{(n-1)/2},-\omega _{n-1)/2}\right\}=\left\{1,\dots ,(n-1)/2,(n+3)/2,\dots ,n\right\},}$

and each diagonal block acts upon a pair of entries of v which are not both zero. So, for example, when n = 3, the matrix can be

- ${\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}0&-1&0\\1&0&0\\0&0&-1\\\end{pmatrix}}.}$

For the vector (1, 0, 1/√2), the resulting simplex has vertices

- ${\displaystyle {\begin{pmatrix}1\\0\\1/\surd 2\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}0\\1\\-1/\surd 2\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}-1\\0\\1/\surd 2\end{pmatrix}},{\begin{pmatrix}0\\-1\\-1/\surd 2\end{pmatrix}},}$

each of which has distance 2 from the others.

|