complex.pdf page 4

|

Apollonius' definition of a circleMain Article: Circle#Circle of ApolloniusProof using vectors in Euclidean spacesLet $d_1,d_2$ be non-equal positive real numbers. Let C be the internal division point of AB in the ratio $d_1:d_2$ and D the external division point of AB in the same ratio, $d_1:d_2$. $$\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PC}} = \frac{d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}+d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}}{d_{2}+d_{1}},\ \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PD}} = \frac{d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}-d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}}{d_{2}-d_{1}}.$$ Then, \begin{aligned} &\mathrm{PA} : \mathrm{PB} = d_{1} : d_{2}. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& d_{2}|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}| = d_{1}|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}|. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& d_{2}^2|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}|^2 = d_{1}^2|\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}|^2. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& (d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}+d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}})\cdot (d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}-d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}})=0. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& \frac{d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}+d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}}{d_{2}+d_{1}}\cdot \frac{d_{2}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PA}}-d_{1}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PB}}}{d_{2}-d_{1}} = 0. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PC}} \cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PD}} = 0. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PC}} = \vec{0} \vee \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PD}} =\vec{0} \vee \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PC}} \perp \overrightarrow{\mathrm{PD}}. \\ \Leftrightarrow{}& \mathrm{P}=\mathrm{C} \vee \mathrm{P}=\mathrm{D} \vee \angle{\mathrm{CPD}}=90^\circ. \end{aligned} Therefore, the point P is on the circle which has the diameter CD.Proof using the angle bisector theoremNext take the other point \(D\) on the extended line \(AB\) that satisfies the ratio. So \(\frac{|AP|}{|BP|}=\frac{|AD|}{|BD|}.\) Also take some other point \(Q\) anywhere on the extended line \(AP\). Also by the Angle bisector theorem the line \(PD\) bisects the exterior angle \(\angle QPB\). Hence, \(\gamma=\angle BPD\) and \(\delta=\angle QPD\) are equal and \(\beta+\gamma=90^{\circ}\). Hence by Thales's theorem \(P\) lies on the circle which has \(CD\) as a diameter. Apollonius pursuit problemThe Apollonius pursuit problem is one of finding whether a ship leaving from one point A at speed \(v_\text{A}\) will intercept another ship leaving a different point B at speed \(v_\text{B}\). The minimum time in interception of the two ships is calculated by means of straight-line paths. If the ships' speeds are held constant, their speed ratio is defined by $μ$. If both ships collide or meet at a future point, \(I\), then the distances of each are related by the equation: \[a = \mu b\] Squaring both sides, we obtain: \[a^{2} = b^{2} \mu^{2}\] \[a^{2} = x^{2} + y^{2}\] \[b^{2} = (d-x)^{2} + y^{2}\] \[x^{2} + y^{2} = [(d-x)^{2} + y^{2}]\mu^{2}\] Expanding: \[x^{2}+y^{2} = [d^{2} + x^{2} - 2dx + y^{2}]\mu^{2}\] Further expansion: \[x^{2} + y^{2} = x^{2} \mu^{2} + y^{2}\mu^{2} + d^{2}\mu^{2} - 2dx \mu^{2}\] Bringing to the left-hand side: \[x^{2} - x^{2}\mu^{2} + y^{2} - y^{2}\mu^{2} - d^{2}\mu^{2} + 2dx\mu^{2} = 0\] Factoring: \[x^{2}(1-\mu^{2}) + y^{2}(1-\mu^{2}) - d^{2}\mu^{2} + 2dx\mu^{2} = 0\] Dividing by \(1-\mu^{2}\) : \[x^{2} + y^{2} - \frac{d^{2}\mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}} + \frac{2dx\mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}} = 0\] Completing the square: \[\left(x+ \frac{d\mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}}\right) ^{2}- \frac{d^{2}\mu^{4}}{(1-\mu^{2})^{2}} - \frac{d^{2} \mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}} + y^{2} = 0\] Bring non-squared terms to the right-hand side: \begin{align*} \left( x + \frac{d\mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}} \right)^{2} + y^{2} &= \frac{d^{2}\mu^{4}}{(1-\mu^{2})^{2}} + \frac{d^{2} \mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}}\\ &= \frac{d^{2} \mu^{4}}{(1-\mu^{2})^{2}} + \frac{d^{2} \mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}} \frac{(1-\mu^{2})}{(1-\mu^{2})}\\ &= \frac{d^{2}\mu^{4}+d^{2}\mu^{2}-d^{2}\mu^{4}}{(1-\mu^{2})^{2}}\\ &= \frac{d^{2} \mu^{2}}{(1-\mu^{2})^{2}} \end{align*} Then: \[\left( x + \frac{d\mu^{2}}{1-\mu^{2}}\right)^{2} + y^{2} = \left( \frac{d \mu}{1-\mu^{2}} \right)^{2}\] Therefore, the point must lie on a circle as defined by Apollonius, with their starting points as the foci. |

|

Geometric interpretation of the bipolar coordinates. The angle $σ$ is formed by the two foci and the point $P$, whereas $τ$ is the logarithm of the ratio of distances to the foci. The corresponding circles of constant $σ$ and $τ$ are shown in red and blue, respectively, and meet at right angles (magenta box); they are orthogonal. DefinitionThe system is based on two foci $F_1$ and $F_2$. Referring to the figure at right, the $σ$-coordinate of a point $P$ equals the angle $F_1PF_2$, and the $τ$-coordinate equals the natural logarithm of the ratio of the distances $d_1$ and $d_2$: $$ \tau = \ln \frac{d_1}{d_2}.$$ If, in the Cartesian system, the foci are taken to lie at $(−a,0)$ and $(a,0)$, the coordinates of the point $P$ are $$ x = a \ \frac{\sinh \tau}{\cosh \tau - \cos \sigma}, \qquad y = a \ \frac{\sin \sigma}{\cosh \tau - \cos \sigma}. $$ The coordinate $τ$ ranges from $-\infty$ (for points close to $F_1$) to $\infty$ (for points close to $F_2$). The coordinate $σ$ is only defined modulo $2π$, and is best taken to range from $-π$ to $π$, by taking it as the negative of the acute angle $F_1PF_2$ if $P$ is in the lower half plane.Proof that coordinate system is orthogonalThe equations for $x$ and $y$ can be combined to give $$ x + i y = a i \cot\left( \frac{\sigma + i \tau}{2}\right). $$ This equation shows that $σ$ and $τ$ are the real and imaginary parts of an analytic function of $x+iy$ (with logarithmic branch points at the foci), which in turn proves (by appeal to the general theory of conformal mapping) (the Cauchy-Riemann equations) that these particular curves of $σ$ and $τ$ intersect at right angles, i.e., that the coordinate system is orthogonal.Reciprocal relationsThe passage from the Cartesian coordinates towards the bipolar coordinates can be done via the following formulas: $$ \tau = \frac{1}{2} \ln \frac{(x + a)^2 + y^2}{(x - a)^2 + y^2} $$ and $$ \pi - \sigma = 2 \arctan \frac{2ay}{a^2 - x^2 - y^2 + \sqrt{(a^2 - x^2 - y^2)^2 + 4 a^2 y^2} }. $$ The coordinates also have the identities: $$ \tanh \tau = \frac{2 a x}{x^2 + y^2 + a^2} $$ and $$ \tan \sigma = \frac{2 a y}{x^2 + y^2 - a^2}. $$ which is the limit one would get a $x = 0$ from the definition in the section above. And all the limits look quite ordinary at $x =0$.Scale factorsTo obtain the scale factors for bipolar coordinates, we take the differential of the equation for $x + iy$, which gives $$ dx + i\, dy = \frac{-ia}{\sin^2\bigl(\tfrac{1}{2}(\sigma + i \tau)\bigr)}(d\sigma +i\,d\tau). $$ Multiplying this equation with its complex conjugate yields $$ (dx)^2 + (dy)^2 = \frac{a^2}{\bigl[2\sin\tfrac{1}{2}\bigl(\sigma + i\tau\bigr) \sin\tfrac{1}{2}\bigl(\sigma - i\tau\bigr)\bigr]^2} \bigl((d\sigma)^2 + (d\tau)^2\bigr). $$ Employing the trigonometric identities for products of sines and cosines, we obtain $$ 2\sin\tfrac{1}{2}\bigl(\sigma + i\tau\bigr) \sin\tfrac{1}{2}\bigl(\sigma - i\tau\bigr) = \cos\sigma - \cosh\tau, $$ from which it follows that $$ (dx)^2 + (dy)^2 = \frac{a^2}{(\cosh \tau - \cos\sigma)^2} \bigl((d\sigma)^2 + (d\tau)^2\bigr). $$ Hence the scale factors for $σ$ and $τ$ are equal, and given by $$ h_\sigma = h_\tau = \frac{a}{\cosh \tau - \cos\sigma}. $$ Many results now follow in quick succession from the general formulae for orthogonal coordinates. Thus, the infinitesimal area element equals $$ dA = \frac{a^2}{\left( \cosh \tau - \cos\sigma \right)^2} \, d\sigma\, d\tau, $$ and the Laplacian is given by $$ \nabla^2 \Phi = \frac{1}{a^2} \left( \cosh \tau - \cos\sigma \right)^2 \left( \frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial \sigma^2} + \frac{\partial^2 \Phi}{\partial \tau^2} \right). $$ Expressions for $\nabla f$, $\nabla \cdot \mathbf{F}$, and $\nabla \times \mathbf{F}$ can be expressed obtained by substituting the scale factors into the general formulae found in orthogonal coordinates. |

|

Circles of Apollonius A set of Apollonian circles. Every blue circle intersects every red circle at a right angle, and vice versa. Every red circle passes through the two foci. Every blue circle passes through the two (imaginary) foci. Indra's Pearls |

回复 3# 其妙 与阿氏圆有关,内角平分线定理和外角是平分线定理构造调和点列的一种手段(还有完全四点形(什么塞瓦、美丽 ... |

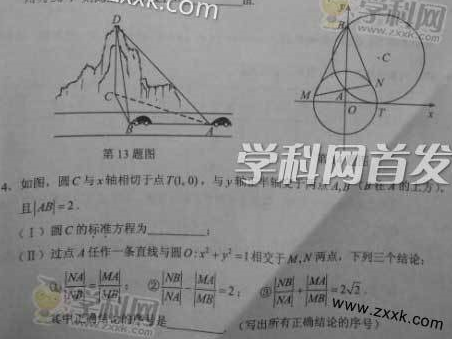

这样的题让考生在高考场上作,出题者扯淡! 初等方法来了:yddy11@人教论坛 4楼: bbs.pep.com.cn/forum.php?mod=viewthread&t … 986&extra=page=1  不过,第1个,无须数字计算的,\[ON^2=OT^2=OA\cdot OB=OM^2\Rightarrow \angle OBN=\angle ONM=\angle OMN=\angle OBM.\] 从而BA是角分线,得到第1个成立。(横向看第1个,分子比分比,分母比分母。) 不过,此法,第2与3又要麻烦些了,因为比值是多少,个人觉得,要借助解几或者阿氏圆来解决。 |

回复 活着&存在 往深处说,就是极线与极点……其实就是这个了。 |

| 这样的题让考生在高考场上作,出题者扯淡! |

| 题目有没有问题?点A是圆C与Y轴的一个交点,过A的直线还要与圆C相交于M、N两点? |

Mobile version|Discuz Math Forum

2025-6-6 13:48 GMT+8

Powered by Discuz!