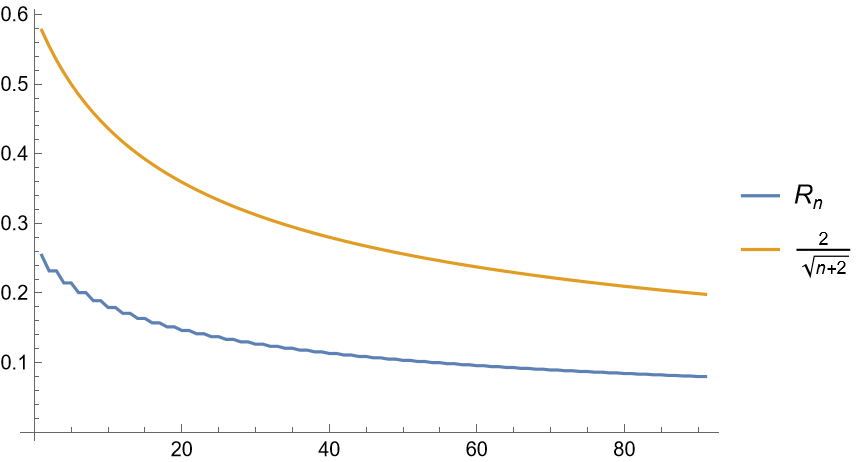

We leave to the reader the task of proving that the remainder after $n$ terms is less than $2 / \sqrt{n+2}$ for $n \geq 10$.

\[\frac{1}{n!} \int_0^1\arcsin^{(n+1)}(t)(1-t)^n\mathrm d t<\frac2{\sqrt{n+2}}\]

- Table[Pi/2.-Normal[Series[ArcSin[t],{t,0,n}]]/.t->1,{n,10,15}]

- Table[1/n! NIntegrate[(1-t)^n(D[ArcSin[x],{x,n+1}]/.x->t),{t,0,1}],{n,10,15}]

- N/@Table[Pi/2-(Normal[Series[ArcSin[t],{t,0,n}]]/.t->1)-2/Sqrt[n+2],{n,10,15}]

- ListLinePlot[{Table[Pi/2-(Normal[Series[ArcSin[t],{t,0,n}]]/.t->1),{n,10,100}],Table[2/Sqrt[n+2],{n,10,100}]}]

|