|

|

An Elementary View of Euler's Summation Formula, Tom M. Apostol

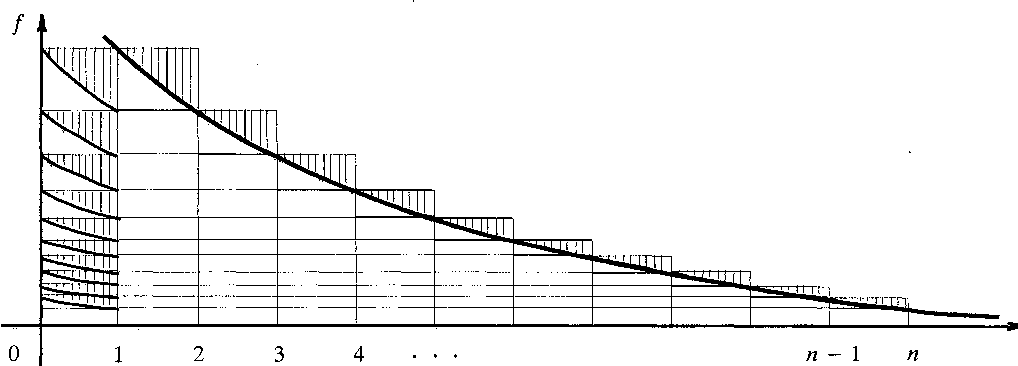

1. INTRODUCTION. The integral test for convergence of infinite series compares a finite sum $\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)$ and an integral $\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x$, where $f$ is positive and strictly decreasing. The difference between a sum and an integral can be represented geometrically, as indicated in Figure 1. In 1736, Euler [3] used a diagram like this to obtain the simplest case of what came to be known as Euler's summation formula, a powerful tool for estimating sums by integrals, and also for evaluating integrals in terms of sums. Later Euler [4] derived a more general version by an analytic method that is very clearly described in [5, pp. 159-161]. Colin Maclaurin [9] discovered the formula independently and used it in his Treatise of Fluxions, published in 1742 , and some authors refer to the result as the Euler-Maclaurin summation formula. The general formula (24) is widely used in numerical analysis, analytic number theory, and the theory of asymptotic expansions. It contains Bernoulli numbers and periodic Bernoulli functions and is ordinarily discussed in courses in advanced calculus or real and complex analysis. This note shows how the general formula can be discovered by an elementary method, beginning with the diagram in Figure 1. This approach also shows how Bernoulli numbers and Bernoulli functions arise naturally along the way. The author has used this treatment successfully with beginning calculus students acquainted with the integral test.

2. GENERALIZED EULER'S CONSTANT. Throughout this section we assume that $f$ is a positive and strictly decreasing function on $[1, \infty)$. We introduce a sequence $\left\{d_{n}\right\}$ of numbers that represent the sum of the areas of the shaded curvilinear pieces above the interval $[1, n]$ in Figure 1 . That is, we define

\begin{equation}

d_{n}=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} f(k)-\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x, \quad n=2,3, \ldots

\end{equation}

Figure 1. All the shaded regions above $[1,n]$ fit inside a rectangle of area $f(1)$. It is clear that $d_{n+1}>d_{n}$ and that all the shaded pieces can be translated to the left to occupy a portion of the rectangle of altitude $f(1)$ above the interval $[0,1]$, as shown in Figure 1. Because $f$ is decreasing there is no overlapping of the translated shaded pieces. Comparison of areas gives us the inequalities $0<d_{n}<d_{n+1}<f(1)$. Therefore $\left\{d_{n}\right\}$ is increasing and bounded above, so it has a finite limit $C(f)=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty} d(n)$. We refer to $C(f)$ as the generalized Euler's constant associated with the function $f$. Geometrically, $C(f)$ represents the sum of the areas of all the curvilinear triangular pieces over the interval $[1, \infty)$. These pieces can be translated to fit inside the rectangle of area $f(1)$ shown in Figure 1 (without overlapping), so we have the inequalities $0<C(f)<f(1)$. Moreover, $C(f)-d_{n}$ represents the sum of the areas of the triangular pieces over the interval $[n, \infty)$. These pieces can be translated to the left to occupy (without overlapping) a portion of the rectangle of height $f(n)$ above the interval $[n, n+1]$. Comparing areas we find

\begin{equation}

0<C(f)-d_{n}<f(n), \quad n=2,3, \ldots

\end{equation}

From these inequalities we can easily deduce:

Theorem 1. If $f$ is positive and strictly decreasing on $[1, \infty)$ there is a positive constant $C(f)<f(1)$ and a sequence $\left\{E_{f}(n)\right\}$, with $0<E_{f}(n)<f(n)$, such that

\begin{equation}

\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)=\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x+C(f)+E_{f}(n), \quad n=2,3, \ldots

\end{equation}

Note. Eq. (3) tells us that the difference between the sum and the integral is equal to a constant (depending on $f$ ) plus a positive quantity $E_{f}(n)$ smaller than the last term in the sum. Hence, if $f(n)$ tends to 0 as $n \rightarrow \infty$, then $E_{f}(n)$ also tends to 0 .

Proof: If we define $E_{f}(n)=f(n)+d_{n}-C(f)$, then (3) follows from the definition (1), and the inequality $0<E_{f}(n)<f(n)$ follows from (2).$■$

If $f(n) \rightarrow 0$ as $n \rightarrow \infty$, then (3) implies

\begin{equation}

C(f)=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)-\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x\right)

\end{equation}

Example. When $f(x)=1 / x, C(f)$ is the classical Euler's constant, often denoted by $C$ (or by $\gamma)$, and (4) states that $C=\lim _{n \rightarrow \infty}\left(\sum_{k=1}^{n}(1 / k)-\log n\right)$. It is not known (to date) whether Euler's constant is rational or irrational. Its numerical value, correct to 20 decimals, is $C=0.57721566490153286060$. In this case, Theorem 1 says that

$$\sum_{k=1}^{n} \frac{1}{k}=\log n+C+E(n), \quad \text { where } 0<E(n)<\frac{1}{n}$$

3. VARIOUS FORMS OF EULER'S SUMMATION FORMULA. In this section we no longer assume that $f$ is positive or decreasing. At the outset we require only that the integral $\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x$ exists for each integer $n \geq 2$. The key insight is to notice that the difference $d_{n}$ in (1) can be written as

\begin{equation}

d_{n}=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} I(k)

\end{equation}

where

\begin{equation}

I(k)=\int_{k}^{k+1}\{f(k)-f(x)\} d x .

\end{equation}

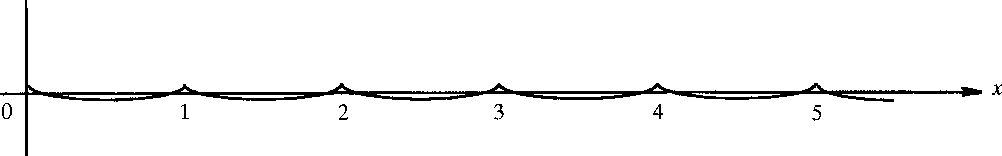

When $f$ is positive and decreasing, as in Figure 2, $I(k)$ is the area of the shaded curvilinear triangular piece over the interval $[k, k+1]$. However, (5) and (6) are meaningful for any integrable $f$.

Figure 2. Geometric interpretation of the integral

$I(k)$ as the area of the shaded region.

$$

I(k)=\int_{k}^{k+1}(x-k-1) f^{\prime}(x) d x .

$$

In this integral the dummy symbol $x$ varies from $k$ to $k+1$, so the quantity $k$ in the integrand can be replaced by $[x]$, the greatest integer $\leq x$. Make this replacement and substitute in (6) to find

$$

\begin{aligned}

d_{n} &=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} I(k)=\sum_{k=1}^{n-1} \int_{k}^{k+1}(x-[x]-1) f^{\prime}(x) d x \\

&=\int_{1}^{n}(x-[x]) f^{\prime}(x) d x-\int_{1}^{n} f^{\prime}(x) d x \\

&=\int_{1}^{n}(x-[x]) f^{\prime}(x) d x+f(1)-f(n)

\end{aligned}

$$

Now use the definition of $d_{n}$ in (1) and rearrange terms to obtain:

Theorem 2. (First-derivative form of Euler's summation formula). For any function $f$ with a continuous derivative on the interval $[1, n]$ we have

\begin{equation}

\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)=\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x+\int_{1}^{n}(x-[x]) f^{\prime}(x) d x+f(1)

\end{equation}

The last two terms on the right represent the error made when the sum on the left is approximated by the integral $\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x$. The formula is useful because $f$ need not be positive or decreasing. In fact, $f$ can be increasing or oscillating. Variants of this formula will be obtained as we attempt to deduce more precise information about the error.

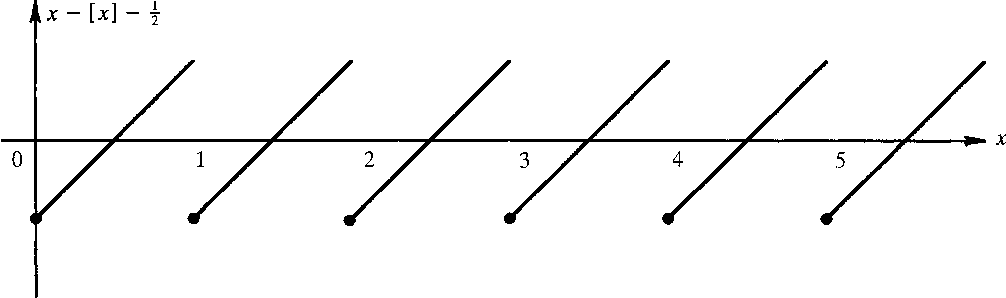

The factor $x-[x]$ is a nonnegative function with period 1 . If $f^{\prime}$ has a fixed sign (as it has when $f$ is monotonic), the integral term in the error has the same sign as $f^{\prime}$. To decrease the error it is preferable to multiply $f^{\prime}(x)$ by a factor that changes sign so that some cancellation takes place in the integration. To introduce sign changes, we translate the function $x-[x]$ down by $\frac{1}{2}$ and consider the new function $x-[x]-\frac{1}{2}$ whose graph is shown in Figure 3 . The integral term in the error can now be written as

$$

\int_{1}^{n}(x-[x]) f^{\prime}(x) d x=\int_{1}^{n}\left(x-[x]-\frac{1}{2}\right) f^{\prime}(x) d x+\frac{1}{2} \int_{1}^{n} f^{\prime}(x) d x

$$

The last term is equal to $\frac{1}{2}\{f(n)-f(1)\}$. Using this in (7) we obtain the following variant of the first-derivative form of Euler's summation formula:

$$

\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)=\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x+\int_{1}^{n}\left(x-[x]-\frac{1}{2}\right) f^{\prime}(x) d x+\frac{1}{2}\{f(n)+f(1)\}

$$

Further variations will be obtained by repeated integration by parts in the second integral on the right of (8).

The factor $x-[x]-\frac{1}{2}$ has the value $-\frac{1}{2}$ when $x$ is an integer. We modify this factor slightly to make it vanish at the integers, a property that is desirable when we integrate by parts. To do this we introduce $P_{1}(x)$, the first Bernoulli function:

$$

P_{1}(x)= \begin{cases}x-[x]-\frac{1}{2} & \text { if } x \neq \text { integer } \\ 0 & \text { if } x=\text { integer. }\end{cases}

$$

The error integral does not change if the factor $x-[x]-\frac{1}{2}$ is replaced by $P_{1}(x)$ because the two factors differ only at the integers. Therefore (8) can be written as

\begin{equation}

\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)=\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x+\int_{1}^{n} P_{1}(x) f^{\prime}(x) d x+\frac{1}{2}\{f(n)+f(1)\}

\end{equation}

Note the contrast between (10) and (3), which explicitly displays the generalized Euler's constant $C(f)$. To make (10) resemble (3) more closely, we assume that the improper integral $\int_{1}^{\infty} P_{1}(x) f^{\prime}(x) d x$ converges. Then we can write

$$

\int_{1}^{n} P_{1}(x) f^{\prime}(x) d x=\int_{1}^{\infty} P_{1}(x) f^{\prime}(x) d x-\int_{n}^{\infty} P_{1}(x) f^{\prime}(x) d x

$$

and (10) takes the form

\begin{equation}

\sum_{k=1}^{n} f(k)=\int_{1}^{n} f(x) d x+C(f)+E_{f}(n)

\end{equation}

Figure 3. The periodic function $x - [x]-\frac12$ changes sign.

Figure 4. Graph of $P_{2}(x)=2 \int_{0}^{x} P_{1}(t) d t+c$ |

|